My recent posts about sorting my library reminded me of an incident earlier this year and how, sometimes, people give you no option about how you judge them.

Usually, selling books involves a day trip to New Hampshire. There is a second-hand bookstore on Route 1 that has a wonderful selection and the owner willingly swaps or buys from me. As an added benefit, he has an impressive collection of jazz recordings and it is a delight to listen to Ornette Coleman, Art Tatum or John Coltrane while browsing.

I had a couple of boxes of books in the back of the car. They were just random reading materials, some trade paperbacks, a few hardcovers, nothing extravagant. But time was short. My wife and I decided to take them to a different store in a nearby town.

I had been avoiding this more convenient bookstore for a very simple reason ... it was too damn tempting. The last time I had been there I had seen a nearly complete collection of the works of E. Phillips Oppenheim, and another of Sax Rohmer. The bookseller had huge masses of wonderful old hardcovers and I wanted them all. These are the kind of books that I find very difficult to dislodge from my shelves and the best defense is self-denial, but I had been diligent about my book purchases long enough, so off we went.

I find that the polite thing to do is to leave the books in the car and ask if they are buying books. Some stores have designated hours, others get overstocked and won't buy for a few weeks. So we left the books in the car.

When we entered the shop, I was bothered. Previously this owner had classical music playing quietly, but now the place was filled with the pablum of easy rock and country.

My wife went to browse through the art and children's books while I checked with the owner. He was a new guy in his mid 30s or early 40s, very fit and proud of it since he was wearing his upscale jogging outfit at work. I asked if he was buying any books and the floodgates opened. He informed me that he ONLY bought trade paperbacks, that he ONLY bought them if they were in perfect condition, that he ONLY bought them in small quantities, etc. Then with a sniff, he also informed me that he didn't buy anything that smelled musty, and punctuating with another sniff he informed me that he never bought books from people who smoked.

"I can't sell books that stink," he said, "people won't buy them. So I doubt that I would buy anything you had."

I wasn't going to argue with him. It was, after all, his bookshop. Other bookshops were happy to take my books. I couldn't help tweaking him a bit though.

"When I worked at a rare book library," I told him, "there was an ongoing research project that suggested that tobacco smoke actually worked as a preservative."

At the prospect of my having some real goodies he started to backtrack. "Well bring them in he said, "Maybe there's something that I'd be interested in."

"No," I said, "I'll just see if you have any books worth preserving," and wandered back to the shelves with the goodies I'd lusted for. They weren't there.

"Where are all the hardcovers?" I asked.

He proceeded to tell me in, agonizing detail, that people didn't buy hardcovers anymore, that they smelled funny, that he didn't like having to research their prices, that he didn't want to get cheated out of their true value just because he didn't have time to price them properly, that they smelled funny, that they looked weird ... and on and on.

"So you sold them off?" I asked a little sadly for having missed the opportunity to bid on the little darlings.

"No." he said, obviously proud of his perspicacity and business acumen. "It cost me thousands, but I had them all sorted out and removed."

"Removed?"

"Stacked in boxes and put into three dumpsters."

My face froze. It must have frozen with an ambiguous expression, since he went on happily to tell me that he had donated the contents of the dumpsters to the Boy Scouts. I relaxed briefly. Then he told me, "Those kids made about fifty dollars after they pulped the ugly smelly th ... "

I turned and left to avoid the impulse to punch his face in. I went out to the car and lit a cigarette (just for the benefit of the books in the back seat). A few seconds later my wife exited the shop, and came and sat down with me.

"That's the last time we go to that place," she said. "What an ass." I couldn't help but agree.

Comments are welcome.

All material on this site that is not otherwise attributed is:

© 2003 - 2017 David W. Lettvin, All rights reserved.

Saturday, August 25, 2007

On Meeting a Biblioclast

Friday, August 24, 2007

The Liberated Library

You might think that I am a bibliomaniac, but that is far from the truth. I am not manic about books. I buy them, sell them, trade them and lend them. I certainly will admit to being a bibliophile, a lover of books.

I have always been a voracious reader, ready to be immersed in the new worlds or alternate visions that books provide. As a writer, I understand that words are a form of power that can be used and abused. So when I find a book that I like, I feel that it imparts some of its power to me. My shelves of books are like my armor, Quixotic armor, rusty and dented, but protective nonetheless.

So disposing of a large part of my library is like stripping away a protective shell, laying myself bare to a world that is not as neatly ordered as my volumes. Like a hermit crab abandoning its shell and trailing its soft abdomen as it searches for another, I feel vulnerable. Unlike J. Alfred Prufrock, I don't particularly want to be a pair of ragged claws, Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

I will also admit to being a collector. The books that I collect are old, but not necessarily expensive. The most I have ever paid for the books that I collect is about $50, and that one was special since it had the bookplate of its previous owner in it; the previous owner being Harpo Marx. (Which reminds me that his brother Groucho once said that, "Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend. Inside of a dog it's too dark too read."

Some that I own I bought for a few dollars at second-hand bookshops only to find later that they were worth hundreds of dollars. Many of these, although dear to me, will be finding new homes.

I am going to think out loud, so to speak, about the process of culling.

My collection consists of quarto-sized books primarily published by The Bodley Head at Oxford, England or Dodd Meade in the US. They are beautifully illustrated fantasies by Cabell, Anatole France and others. They are staying with me, as are the complete sets of Sir Richard Burton's translation of "A Thousand Nights and A Night" and Fraser's "The Golden Bough".

Much of the poetry will go. The books on technical writing, semiotics, linguistics and much of the science and math will descend into the cardboard purgatory with most of the religion and philosophy.

The reference books stay. So what if I have three rhyming dictionaries ... they stay. The books on colonial history, agriculture and architecture stay.

Most of the novels will go except for those that would be nearly impossible to replace. Probably half the books on design will also find new homes.

The easiest to dispose of and the first to be packed will be the collection of books that I have written. It's not as horrifying as it sounds. I spent many years as a technical writer and wrote hundreds of software manuals, marketing guides, reference books, and contributed papers to many periodicals and proceedings. All of them are outdated and although I am proud of the work, they are now meaningless.

Ah me ... I know that I am doing the logical thing, but my heart disagrees with my head. Logic is like the the curate and the barber in Don Quixote, sorting and consigning the mad knight's books to the fire as he lies sleeping.

"That night the housekeeper burned to ashes all the books that were in the yard and in the whole house; and some must have been consumed that deserved preservation in everlasting archives, but their fate and the laziness of the examiner did not permit it, and so in them was verified the proverb that the innocent suffer for the guilty.

One of the remedies which the curate and the barber immediately applied to their friend's disorder was to wall up and plaster the room where the books (had been), so that when he got up he should not find them (possibly the cause being removed the effect might cease), and they might say that a magician had carried them off, room and all; and this was done with all despatch. Two days later Don Quixote got up, and the first thing he did was to go and look at his books, and not finding the room where he had left it, he wandered from side to side looking for it. He came to the place where the door used to be, and tried it with his hands, and turned and twisted his eyes in every direction without saying a word; but after a good while he asked his housekeeper whereabouts was the room that held his books.

The housekeeper, who had been already well instructed in what she was to answer, said, 'What room or what nothing is it that your worship is looking for? There are neither room nor books in this house now, for the devil himself has carried all away.'"

But this is no destruction. My wife has no kindling at hand. There will be no garden conflagration ... except, perhaps for the trivial instructions I have penned. Although, if they are to burn, it will be by my hand. I will not make a Lady Burton out of her; putting her husband's manuscripts (no matter how trivial) to the torch.

No, these orphan books shall go to good homes, shall be adopted by bibliophiles more settled and secure. I send them off with a quote from Richard LeGallienne:

"Thus shall you live upon warm shelves again,

And 'neath an evening lamp your pages glow."

Thursday, August 23, 2007

The Bookman's Melancholy

I am in the process of decimating my library. Actually, it's worse than that. I have had to set myself the goal of reducing my collection of books by at least two thirds.

This is a painful process for someone whose life has always centered around the written word, both his own and others. Don't misunderstand me, I appreciate a good movie, and although I seldom watch television these days, I enjoy some of it quite a bit.

But I grew up with books, and they are my first love. My parents say that I first started to read on my own when I was three-years-old. By the time I was in 5th grade, my bedroom was filled with bookshelves from wall to wall. As a freshman in high school, I was the only person other than the librarians to have a stack pass to the city library. (They told me that it was self-defense since I read so much and such varied subjects that it was easier to let me get my own books than for them to be constantly searching out yet another obscure book.)

The size of my personal library peaked many years ago at about 10,000 or so volumes. Since then I have tried to impose some discipline. Until then, any book that I liked, or thought that I might like better in the future, or that I thought I might need for research, etc. could easily find itself a home on my shelves. Well actually it would have had to be a book that was intolerably bad in some way not to achieve at least a temporary adoption.

These days, I try hard to be diligent about culling but, I probably have over one thousand books in this room alone, and another 500 or so scattered elsewhere throughout the house. Several of my bookshelves are stacked two layers deep.

People don't read as much as they used to, or so I am told. I guess that must be true since even the well-read among my friends are startled by the volume of books on the walls of my study. I must be out-of-date.

I have mentioned before, when in a listing frame of mind, some of the books that live here with me, so I will not revisit them all. But to return to the subject of this blog, I would like to examine here the melancholia of a bookman in the process of divorcing his companions.

Here is, as the King of Siam would put it, a puzzlement. I have three copies of Rabelais' works. Each contains the same text translated by the same translator, yet each has its own unique charm. Which of them shall be sent away, expelled from its place on the shelf? How am I to make a choice?

The first cut is easy. One of the copies is a paperback used only for reading to save wear and tear on the other two. With only a small pang I place the tattered Penguin paperback into the box to be joined later by other outcasts.

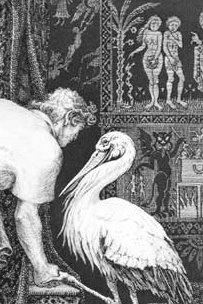

But the second choice is hard. The two hardcover books sit next to me as I write, waiting to learn their fate. The smaller is covered in brown cloth with goldleaf title on the spine and an illustration in gold on the front cover. Published by Chatto and Windus in 1879, it contains "numerous" illustrations by the great Gustave Dore. Illustrations even more delightful than those he made for Dante's "Divine Comedy". They are wicked, bawdy, and powerful.

... and yet ...

The book with the red cover has no date on it, but I know that it was published in 1927. It contains the same text, but this one was illustrated by Frank C Pape, an artist now mostly forgotten except by a few fanatics (in whose company I eagerly count myself). He is an illustrator whose delightfully vicious sense of humor was so perfect that James Branch Cabell once wrote him a letter apologizing that his text was no match for Pape's illustrations.

How do I choose between them?

The simple answer is ... I cannot. I place the two books back on the shelf.

My wife comes in to see how my task is progressing. She looks in the box at the single paperback, laughs and shakes her head. She pats me on the shoulder, kisses my on the ear and tells me to keep up the good work.